KN Magazine: Interviews

“Robert Mangeot: Short Stories and the Big Honking Moment”

Robert Mangeot interviewed by Clay Stafford

Since the inception of Killer Nashville, the name of Robert Mangeot has been a constant presence, a beacon of inspiration for aspiring short story authors. His literary prowess has been recognized in various anthologies and journals, including the prestigious Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, The Forge Literary Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Mystery Magazine, The Oddville Press, and in the print anthologies Die Laughing, Mystery Writers of America Presents Ice Cold: Tales of Intrigue from the Cold War, Not So Fast, and the Anthony-winning Murder Under the Oaks. His work has been honored with the Claymore Award, and he is a three-time finalist for the Derringer Awards. He’s also emerged victorious in contests sponsored by the Chattanooga Writers’ Guild, On the Premises, and Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. His pedigree in the realm of short stories is truly unparalleled.

“So, Bob, how are short stories different from novels other than the length?”

“They are entirely different organisms. Novels, done right, are interesting explorations of something: theme, a place, a premise. The novel will view things from multiple angles. Short stories may, too, but novels will explore connected subplots. They might have many points of view on the same crime or the same big event, or whatever the core thing of the story is so that you get an intense picture of the idea of what this author is trying to convey, even if it's just to have a good time. Novels are an exploration. And they will take their time. I'm not saying they're low on conflict, but they will take their time to develop the clues, develop characters, and introduce subplots. Potentially, none of that is in a short story, right? The short story is not a single-cell organism but a much smaller one in that everything is all part of the same idea.”

“How do you get it all in but make it shorter?”

“There aren't subplots. There are as few characters as you can get away with. Once you get those baseline things down, it’s about compression. No signs, no subplots. Just keep on that straight line between the beginning and ending. Once you've mastered that, there's a bazillion ways to go about it, but you must meet those baselines. Everything connects to the whole, and—I know I overuse this—but the construct that I always go back to is Edgar Allen Poe. He called it unity of effect. He often talked about emotion, so he wanted to create a sense of dread. Everything in the story was to build that up.”

“And that’s your basis?”

“For me, the whole unity is what the story tries to convey. It can be heavy-handed. It can be lighthearted. But the characters should reflect that idea by who they are, where they live, how old they are, whether they have family or not, what's the story's tone, what's the crime in the story, and what the murder weapon of the crime is. Everything connects to the whole. I can assess that in my own stories, if I introduce something—an object, a character, a place— I don't just use it once; I use it twice. And if I can't use it twice seamlessly, it's either not important, and thus I don't need to play it up, or it is important because now there's something to that, right? Then, you can begin to explore that. Some editing is for flow, but some ensure this whole thing comes together. Because, you know, readers are going to notice. Clay, you're a fast reader, but you won't read an 80,000-word novel in a night, right?”

“Not unless I have an interview or a story meeting the next day.”

“Right! You'll read that over several days, a week, or something like that.”

“Yes.”

“A short story is something you'll read in twenty minutes or fifteen minutes, and you’ll know if something is off about that story. That's part of the magic of the short story. You’re going to pull off that trick for the reader. You’ve got to grab them. You're not going to have to hold them for long, but any little slip and the magic is gone, and they're out of the story.”

“What unifies the short story? Is it a theme, or what?”

“I tend to think it would be thematic. It would almost have to be. It could be a place, but it must still be about something. Why did you pick the place?”

“Which seems thematic.”

“Yeah, right. You asked the question earlier about how I get started on a story. It’s not some abstract idea. It's not that I want to write about love or family. I think some of that comes out.”

“So what is it?”

“Voice. Voice means two different things. One of them is personal, and one is technical. In terms of your sense of voice, what choices do you make? What do you naturally write about even if you're unaware you're writing about it? What comes up repeatedly in my stories, and I don't intend to do it, is families. Even in stories when it's not necessarily a biological family. I don't know what that says about me. I have great parents. But that tends to be what it is. So, if people can step back in the story and say, ‘Oh, well, this was about love and the price of it,’ then I think I did it.”

“Do you have room in a short story for character arcs?”

“The characters must grow. They must be tested. The structure that I use in most of my stories—I hope it's not obvious, but probably is for people who understand structure—is the three-act structure. So, someone has a problem. That problem has changed their world. And then you get to try to solve the problem, and it gets worse, and it gets worse, and it gets worse. In short stories, it will be a problem you can resolve in 3,000 words, 5,000 words, or 1,000 words if you're writing short. There's going to be moments of conflict. And that's where characterization comes in. Of course, they can't win unless it's a happy story where they win. But how do those setbacks and their trials to set things right—even if it's the wrong decision—go back to the way things were, to embrace a change, and how do they think about that? That's what I like about writing. I think that's where the conflict comes from short stories. That's the story's core: how they will confront it. How does it change them? Does it leave them for the better or worse? And typically, in most of my stories, it’s for the better. Either way, throwing them more problems is the same arc, which'll keep making it more complicated.”

“It keeps building?”

“You can't let the reader rest in a short story, but you can give moments where the character has a little time to reflect. A paragraph, right? ‘Oh, my God, this has happened. Now, what am I going to do?’ So the readers can catch their breath there along with the character, and then back to a million miles an hour. I'll go back to voice. There's the personal side of voice. The words you choose, the topics you choose, even when unaware of those choices. That's your voice. And then there's what I would call narrative voice, which I think is underappreciated as a tool in the short story. The great writers all know how to do it, even if they don't know they're doing it that way. However, one way to achieve compression in a story is not by any of the events you have or don't have; it's how the narrator tells the story. Suppose the narrative voice carries a certain tone, a certain slant, and a certain kind of characterization. In that case, that's going to superpower compression throughout the whole story because people will get the angle that the story is coming from, and then you don't have to explain so much.”

“Easier said than done, of course. So, what are the advantages, if any, of writing short stories over longer forms?”

“They are a wonderful place to experiment. I've written a couple of novels. I would never try to sell them now because I wrote them when I first started writing, and they're not any good. I would have to rewrite them. If I dedicated all my writing to a novel, it’d take me a couple of years to write one. There's no guarantee it would be any good. If my goal is publication, there'd be no guarantee an agent would like it. Then there's no guarantee a publisher would take it or it would sell well; all of those have no guarantees, right? And so, you could get into this thing and have a lot of heartbreak. And then you say, well, I will try it again.”

“And maybe the same thing happens. Trunk novels.”

“With short stories, you can just try it. It's going to take you a few days to write it. I put a lot of angst into the editing bit. A lot of people are better at that than I am. And if it doesn't work, so what? You've talked to yourself a lot about writing. I’ve learned this sort of story isn’t for me, but I'm getting better at it, getting better at it, getting better at it. There's not a lot of money in this stuff. So why not have some fun? Why not experiment?”

“Do you think that writers of short stories have more flexibility in the types of things they can do? And I'm asking this because one of the things I've lamented about the literary industry is that you get known for a certain thing. However, a filmmaker, for example, can make any number of styles of movies, and nobody ever pays attention to the fact. They are usually just attracted to the stars or whoever is in the movie. However, the filmmaker and the writer can be diverse in whatever interests them. Do you think there's more flexibility in being a short story writer?”

“There is. A great example is Jeffrey Deaver.”

“My songwriting buddy.”

“Yes. When he's writing novels, he's Jeffrey Deaver, right? He's the brand and has to deliver a very certain thing. But read some of the short stories. They're terrific. And they're not some of these same characters.”

“Do you think it's difficult for a novelist to write a short story and a short story writer to write a novel? If somebody is used to writing long, can they cut it short? Or can they fill it in after writing short to make it long?”

“You know, people can't be great at everything. Some people are naturally better at short. I suspect I'm one of them. Some people are naturally better at long. But I would also say that if you know how to write, you’ll figure out either form. You can figure out poetry. You can figure out creative nonfiction. If you're a writer, you can write.”

“What’s the most important thing, the most important element, in a short story?”

“Endings are the most important at any length, but short stories are all they are. They exist to give you a big moment of catharsis, release, insight, whatever it is, that you get at the end of a perfect story. Anyone who's a big reader knows what I’m talking about. You get that thing at the end of the story. That's really all short stories are at the end of the day. That's what they're there to do. To produce that moment. And so, I always call it the big honking moment. You light the rocket right at the beginning, and that big honking moment is when the fireworks go off. And it exists to do that and to do it quickly. That's what the payoff and all this planning is about. And people do it in wonderful ways.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Robert Mangeot’s short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, The Forge Literary Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Mystery Magazine, the MWA anthology Ice Cold, and Murder Under the Oaks. His work has been nominated three times for a Derringer Award and, in 2023, received a Killer Nashville Claymore Award. https://robertmangeot.com/

“Dean Koontz: The Secret of Selling 500 Million Books”

Dean Koontz interviewed by Clay Stafford

Dean Koontz is and always has been an incredibly prolific writer. He’s also an excellent writer, which explains why he’s had such phenomenal success. When I heard he and I were going to get to chat exclusively for Killer Nashville Magazine, I wanted to talk to him about how one man can author over one hundred and forty books, a gazillion short stories, have sixteen movies made from his books, and sell over five hundred million copies of his books in at least thirty-eight languages. It's no small feat, but surprisingly, one that Dean thinks we are all capable of. “So, Dean, how long should a wannabe writer give their career before they expect decent results?”

“Well, it varies for everybody. But six months is ridiculous. Yeah, it’s not going to be that fast unless you’re one of the very lucky ones who comes out, delivers a manuscript, and publishers want it. But you also have to keep in mind some key things. Publishers don’t always know what the public wants. In fact, you could argue that half the time, they have no idea. A perfect example of this is Harry Potter, which every publisher in New York turned down, and it went to this little Canadian Scholastic thing and became the biggest thing of its generation. So, you just don’t know. But you could struggle for a long time trying to break through, especially for doing anything a little bit different. And everybody says, ‘Well, this is different. Nobody wants something like this.’ And there are all those kinds of stories, so I can’t put a time frame on it. But I would say a minimum of a few years.”

“I usually tell everyone—people who come to Killer Nashville, groups I speak to—four years. Give it four years. Is that reasonable?”

“I think that's reasonable. If it isn’t working in four years, I wouldn’t rule it out altogether, but you’d better find a day job.”

“I was looking at your Facebook page, and it said on some of your books you would work fifty hours a week for x-amount of time, seventy hours a week for x-amount of time. How many hours a week do you actually work?”

“These days, I put in about sixty hours a week. And I’m seventy-eight.”

“Holy cow, you don’t look anywhere near seventy-eight.”

He shakes his head. “There’s no retiring in this. I love what I do, so I’ll keep doing it until I fall dead on the keyboard. There were years when I put in eighty-hour weeks. Now, that sounds grueling. Sixty hours these days probably sounds grueling to most people or to many people. But the fact is, I love what I do, and it’s fun. And if it’s fun, that doesn't mean it’s not hard work and it doesn’t take time, because it’s both fun and hard work, but because it is, the sixty hours fly by. I never feel like I’m in drudgery. So, it varies for everybody. But that’s the time that I put in. When people say, ‘Wow! You’ve written all these books; you must dash them off quickly.’ No, it’s exactly the opposite. But I just put a lot of hours in every week, and it’s that consistency week after week after week. I don’t take off a month for Bermuda. I don't like to travel, so that wouldn't come up anyway. When you do that, it’s kind of astonishing how much work piles up.”

“How is your work schedule divided? I assume you write every single day?”

“Pretty much. I will certainly write six days a week. I get up at 5:00. I used to be a night guy, but after I got married, I became a day guy because my wife is a day person. I’m up at 5:00, take the dog for a walk, feed the dog, shower, and am at my desk by 6:30, and I write straight through to dinner. I never eat lunch because eating lunch makes me foggy, and so I’m looking at ten hours a day, six days a week, and when it’s toward the last third of a book, it goes to seven days a week because the momentum is such that I don’t want to lose it. It usually takes me five months to six months to produce a novel that’s one hundred thousand words.”

“Does this include your editing, any kind of research you do, and all that? Is it in that time period?”

“Yeah, I have a weird way of writing; though, I’ve learned that certain other writers have it. I don’t write a first draft and go back. I polish a page twenty to thirty times, sometimes ten, but I don’t move on from that page until I feel it’s as perfect as I can make it. Then I go to the next page. And I sort of say, I build a book like coral reefs are built, all these little dead skeletons piling on top of each other, and at the end of a chapter, I go print it out because you see things printed out you don’t see on the screen. I do a couple of passes of each chapter that way and then move on. In the end, it’s had so many drafts before anyone else sees it that I generally never have to do much of anything else. I’ll always get editorial suggestions. I think since I started working this way, which was in the early days, my editorial suggestions take me never a lot more than a week, sometimes a couple of days. But when editors make good suggestions, you want to do it because the book does not say ‘By Dean Koontz with wonderful suggestions by…’ You get all the credit, so you might as well take any wonderful suggestion.”

“You get all the blame, too.”

“Yes, you do, although I refuse to accept it.”

“Do you work from an outline, then? Or do you just stream of consciousness?”

“I worked from outline for many years, but things were not succeeding, and so I finally said, you know, one of the problems is that I do an outline, the publisher sees it, says ‘Good. We’ll give you a contract,’ then I go and write the book and deliver it, and it’s not the same book. It’s very similar, but there are all kinds of things, I think, that became better in the writing, and publishers say, ‘Well, this isn’t quite the book we bought,’ and I became very frustrated with that. I also began to think, ‘This is not organic. I am deciding the entire novel before I start it.’ Writing from an outline might work and does for many writers, but I realized it didn’t work for me because I wasn’t getting an organic story. The characters weren’t as rich as I wanted because they were sort of set at the beginning. So, I started writing the first book I did without an outline called Strangers, which was over two hundred fifty thousand words. It was a long novel and had about twelve main characters. It was a big storyline, and I found that it all fell together perfectly well. It took me eleven months of sixty- to seventy-hour weeks, but the book came together, and that was my first hardcover bestseller. I’ve never used an outline since. I just begin with a premise, a character or two, and follow it all. It’s all about character, anyway. If the book is good, character is what drives it.”

“Is that the secret of it all? Putting in the time? Free-flowing thought? Characters?”

“I think there are several. It’s just willing to put in the time and think about what you’re doing, recognizing that characters are more important than anything else. If the characters work, the book will work. If the characters don’t, you may still be able to sell the book, but you’re not looking at long-term reader involvement. Readers like to fall in love with the characters. That doesn’t mean the characters all have to be wonderful angelic figures. They also like to fall in love with the villains, which means getting all those characters to be rich and different. I get asked often, ‘You have so many eccentric characters. The Odd Thomas books are filled with almost nothing else. How do you make them relatable?’ And I say, ‘Well, first, you need to realize every single human being on the planet is eccentric. You are as well.”

“Me?” I laugh. “You’re the first to point that out.”

He joins in. “It’s just a matter of recognizing that. And then, when you start looking for the characters’ eccentricities—which the character will start to express to you—you have to write them with respect and compassion. You don’t make fun of them, even if they are amusing, and you treat them as you would people: by the Golden Rule. And if you do, audiences fall in love with them, and they stay with you to see who you will write about next. And that’s about the best thing I can say. Don’t write a novel where the guy’s a CIA agent, and that’s it. Who is he? What is he other than that? And I never write about CIA agents, but I see there’s a tendency in that kind of fiction to just put the character out there. That’s who he is. Well, that isn’t who he is. He’s something, all of us are, something much more than our job.”

“What advice do you give to new writers who want to become the next Dean Koontz?”

“First of all, you can’t be me because I’m learning to clone myself, so I plan to be around for a long time. But, you know, everybody works a different way, so I’m always hesitant to give ironclad advice. But what I do say to many young writers who write to me, and they’ve got writer's block, is that I’ve never had it, but I know what it is. It’s always the same thing. It’s self-doubt. You get into a story. You start doubting that you can do this, that this works, that that works. It’s all self-doubt. I have more self-doubt than any writer I’ve ever known, and that’s why I came up with this thing of perfecting every page until I move to the next. Then, the self-doubt goes away because the page flows, and when I get to the next page, self-doubt returns. So, I will do it all again. When I’m done, the book works. Now, if that won’t work for everybody, I think it could work for most writers if they get used to it, and there are certain benefits to it. You do not have to write multiple drafts after you’ve written one. What happens with a lot of writers is they write that first draft—especially when they’re young or new—and now they have something, and they’re very reluctant to think, ‘Oh, this needs a lot of work’ because they’re looking at it as, ‘Oh, I have a novel-length manuscript.’ Well, that’s only the first part of the journey. And I just don’t want to get to that point and feel tempted to say, ‘This is good enough,’ because it almost never will be that way.”

“No,” I say, “it never will.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Dean Koontz is the author of many #1 bestsellers. His books have sold over five hundred million copies in thirty-eight languages, and The Times (of London) has called him a “literary juggler.” He lives in Southern California with his wife Gerda, their golden retriever, Elsa, and the enduring spirits of their goldens Trixie and Anna. https://www.deankoontz.com/

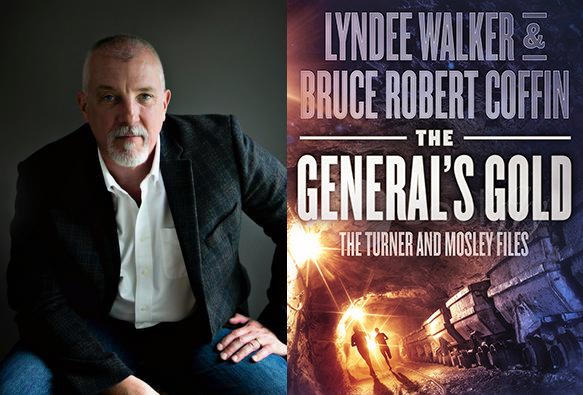

“Bruce Robert Coffin: Using Your Life to Write a Police Procedural”

Bruce Robert Coffin interviewed by Clay Stafford

Bruce Robert Coffin has been coming to Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference every year since its early days, so it’s only fitting that we feature this incredibly talented writer as our cover story. To give a little backstory, Bruce wanted to be a writer, but after going to college and not necessarily receiving the encouragement or success he had hoped for, he chose a career in law enforcement. Little did he realize he was laying the foundation for the outstanding writing career that was to follow. I had a chance to speak with Bruce from his home in Maine. “Bruce, when you were a police officer, a detective, did you even think about writing again, or did you miss writing as you went through your regular job?”

“There’s nothing fun about writing in police work or detective work. Everything is bare bones. There’s not much room for adjectives or that type of stuff. It’s just the facts, ma’am. That’s what they expect out of you. So, everything is boilerplate. It’s very boring. You’re taking statements all the time. You’re writing. If there was one similar thing, and it certainly didn’t occur to me that there would ever be a time that I would write fiction again, but it did teach me to write cohesively. Everything that we did had to make sense. You know, you do one thing before you do the next. Building timelines for putting a case together, doing interviews with witnesses, and then figuring out how they all fit together, and making a cohesive story or narrative out of that to explain to a judge, a jury, or a prosecutor. As far as story building was concerned, I think that might have been something I was learning at that point because that’s exactly how a real case gets made. I wasn’t thinking about it in terms of writing later, but I think it’s something that helped me because I think my brain works that way now. I know how cases will work, I know how cases are solved, and I know why cases stall out. I think all those things really allow me to better describe what real police work is like in my fictional novels.”

“When you retired from detective work and started writing again, how much of the police work transferred over, and how much was fiction from your head?”

“I made a deal with myself when I started that I wouldn’t write anything based on a real case. I had had enough of true crime. I had seen what the real-life cases had done to people: the survivors, the victims, the families, and I didn’t want to do anything that would cause people pain by fictionalizing something that had been part of their lives. I made a deal with myself that I would write as realistically as possible, but I would never base any books on an actual case I had worked on. And I’ve so far, knock on wood, been able to stand by that. I think the only exception would be if it were something that had a reason. Maybe the family came to me and asked me to do that or something like that. There had to be a reason for it, though. And so, when I started writing, I could draw from a well of a million experiences, things that we tamp down deep inside, and you don’t think about how that affects who I am and how I see the world. And I think in my mind, I imagined I would be making up stuff, and that would be it. There’s nothing but my imagination. There would be nothing personal about what I was writing, and it would just be fun. And like everything you delve into that you don’t actually know, I had no idea I would be diving into the real stuff, like dipping the ladle into that emotional well and pulling out chunks of things from my past. There were scenes that I wrote that emotionally moved me as I was writing them. And it’s because what I’m writing is based on something that happened in real life. And I’m crafting it to fit into the narrative of the story I’m writing. But the goal of me doing that is really to evoke emotion from the reader, which I think is the most important thing any of us can do. You want the reader to feel something. You want them to be lost in your story. And I really didn’t think that was going to happen. But it’s amazing what I dredged up and continued to dredge up as I write these fictional police procedural stories.”

“Some of the writers I talk with view writing as therapy. Did you find it cathartic coming from your previous life?”

“I did. I think that was another shock. I didn’t think any catharsis was involved in what I was doing. But like I say, when you start delving back into things that you thought you had either forgotten about or thought were long past, it really allowed me to deal with things. It allowed me to deal with things I wasn’t happy about when I left the job. The things that I wish I could unsee or un-experience. As a writer, I was able to pull from those. I think you and I have talked about this in the past. I honestly think the best writing comes from adversity. Anything difficult that the writers have gone through in life translates well to the page. And I think that’s one of those things where, if you can insert those moments into your characters’ lives, your reader can’t help but identify with them. So, I just had the luxury of having the life we all have, the ups and downs, the highs and lows, the death and the love, and all those things we have to experience. But added to that, I had thirty years of a crazy front-row seat to the world as a law enforcement officer. So, using all of that, I think, has made my stories much more realistic and maybe more entertaining because it gives the reader a glimpse inside what that world is really like.”

“So, you have this front-row seat. And then we readers read that, and we want to write that. But we haven’t had that experience. Is it even possible for us to get to that point that we could write something like that?”

“It is. And I tell people that all the time. I say you have to channel your experiences differently, I think. Like I said, we all have experiences, things that are heart-wrenching, or things that are horrifying, or whatever it is in our lives. They just don’t happen with as great a frequency as they would happen for a police officer. And we all know what it’s like to be frustrated working for a business, being part of a dysfunctional family, or whatever it is. Everybody has something. And so, I tell people to use that. Use that in your stories and try to imagine. You know, you can learn the procedure. You might not have those real-world experiences, but you can learn the procedure, especially from reading other writers who do it well. But use your own experiences. Insert that in there. You know, one of the things that I think is the easiest for people to think about is how hard it is to try and hold down a job. Like, you go to work, and you may see the most horrific murder happen, and you’re dealing with the angst that the family or witness is suffering, and you’re carrying that with you. Then you come home and try to deal with a real-world where other people don’t see that stuff. Like your spouse is worried that the dishwasher is leaking water under the kitchen floor, and that’s the worst thing that’s happened all day, right? That the house is stressed out because of that. And it’s hard to come home. It’s almost like you have to lead a split personality. It’s hard to come home and show the empathy that your spouse needs for that particular tragedy when you’re carrying all those other tragedies from the day. And you won’t share those with them because you don’t want that darkness in your house. I tell people to try to envision what that would be like and then pull from their own life the adversity they’ve experienced or seen and use that to make the story and the characters real. You can steal the procedure from good books. Get to know your local law enforcement officer, somebody who’s actually squared away and will share that information with you. Don’t get it from television necessarily. Some of TV writing is laziness. Some of it’s because they have a very short time constraint to try and get the story told. So, they take huge liberties with reality. But if you can take that stuff and try to put yourself in the shoes of the detective and use your own experiences, you can bring a detective to life.”

“You think anybody can do it?”

“I do. I do think that you have to pull from the right parts of your life. And again, as I say, if you spend enough time with somebody who’s done the job and get them to tell you, it’s not just what we do. It’s how we feel. And the feeling, I think, is what’s missing from those stories many times. If you want to tell a real gritty police detective story, you have to have feeling in that. That’s the one thing we all pretend we don’t have. You know, we keep the stone face. We go to work, do our thing, and pretend to be the counselor or the person doing the interrogation. But at the end of the day, we’re still just human beings. And we’re absorbing all these things like everybody else does. So yeah, you have to see that. Get to hear that from somebody for real, and you’ll know what will make your detective tick.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Bruce Robert Coffin is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. A retired detective sergeant, Bruce is the author of the Detective Byron Mysteries, co-author of the Turner and Mosley Files with LynDee Walker, and author of the forthcoming Detective Justice Mysteries. His short fiction has appeared in a dozen anthologies, including Best American Mystery Stories, 2016. http://www.brucerobertcoffin.com/

“A Casual Conversation with Susan Isaacs”

Susan Isaacs interviewed by Clay Stafford

I had a wonderful opportunity to just chat with bestselling author and mystery legend, Susan Isaacs, as a follow-up to my interview with her for my monthly Writer’s Digest column. It was a wonderful conversation. I needed a break from writing. She needed a break from writing. Like a fly on the wall (and with Susan’s permission), I thought I’d share the highlights of our conversation here with you.

“Susan, I just finished Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown. I loved it. And I now have singer Jim Croce’s earworm in my head.”

“Me, too.” She laughed.

“I love your descriptions in your prose. Right on the mark. Not too much, not too little.”

“Description can be hard.”

“But you do it so well. Any tips?”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I do. Two things. First, I see it in my head. I’m looking at the draft, and I say, ‘Hey, you know, there’s nothing here.’”

I laugh. “So, what do you do?”

“Well in Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown, the character with the problem is a college professor, a really nice woman, who teaches film, and her area of specialization is big Hollywood Studio films. When she was five, her parents were murdered. It was an arson murder, and she was lucky enough to jump out of the window of the house and save herself. So, Corie, who’s my detective, a former FBI agent, is called on, but not through herself, but through her dad, who’s a retired NYPD detective. He was a detective twenty years earlier, interviewing this little girl, April is her name, and they kept up a kind of birthday-card-Christmas-card relationship.”

“And the plot is great.”

“Thanks, but in terms of description, there was nothing there. But there were so many things to work with. So, after I get that structure, I see it in my head, and I begin to type it in.”

“The description?”

“Plot, then description.”

“And you mentioned another thing you do?”

“Research. And you don’t always have to physically go somewhere to do it. I had a great time with this novel. For example, it was during COVID, and nobody was holding a gun to my head and saying ‘Write’ so I had the leisure time to look at real estate in New Brunswick online, and I found the house with pictures that I knew April should live in, and that’s simply it. And I used that house because now April is being threatened, someone is trying to kill her twenty years after her parent’s death. Though the local cops are convinced it had nothing to do with her parents’ murder, but that’s why Corie’s dad and Corie get pulled into it.”

“So basically, when you do description, you get the structure, the bones of your plot, and then you go back and both imagine and research, at your leisure, the details that really set your writing off. What’s the hardest thing for you as a writer?”

“You know, I think there are all sorts of things that are hard for writers. For me, it’s plot. I’ll spend much more time on plot, you know, working it out, both from the detective’s point-of-view and the killer’s point-of-view, just so it seems whole, and it seems that what I write could have happened. For me, I don’t want somebody clapping their palm to their forehead and saying, ‘Oh, please!’ So that’s the hard thing for me.”

“You’ve talked with me about how focused you get when you’re writing.”

“Oh, yes. When you’re writing, you’re really concentrating. We were having work done on the house once and they were trying to do something in the basement, I forget what it was. But there was this jackhammer going, and I was upstairs working. It was when my kids were really young and, you know, I had only a limited amount of time to write every day, and so I was writing and I didn’t even hear the jackhammer until, I don’t know, the dog put her nose or snout on my knee and I stopped writing for a moment and said, ‘What is that?’ and then I heard it.”

“But it took your dog to bring you out of your zone. Not the jackhammer.”

“You get really involved.”

“Sort of transcending into another universe.”

“The story pulls you in. The weird thing is that I have ADD, ADHD, whatever they call it. I know that now, but I didn’t know that then, back when the jackhammer was in the basement. In fact, I didn’t know there was a name for it. I just thought, ‘This is how I am.’ You know, I go from one thing to the next. But people with ADHD can’t use that as an excuse not to write because you hyper-focus.”

“That’s interesting.”

“You don’t hear the jackhammers.”

“So things just flow.”

“Well, it’s always better in your head than on the page,” she says, “as far as writing goes.”

“I’d love to see your stories in your head, then, because your writing is great. As far as plotting, the book moves along at a fast clip. I noticed, distinctly, that your writing style is high with active verbs. Is that intentional or is that something that just comes naturally from you?”

“I think for me it just happens. It’s part of the plotting.”

“Well, it certainly moves the story forward.”

“Yes, I can see it would. But, no, I don’t think ‘let me think of an active verb’. You know,” she laughs, “I don’t think it ever occurred to me to even think of an active verb.”

“That’s funny. We’re all made so differently. I find it fascinating that, after all you’ve published, your Corie Geller novel is going to be part of the first series you’ve ever written. Everything else has been standalones.”

“Yes. I’m already writing the next book. Look, for forty-five years, I did mysteries. I did sagas. I did espionage novels. I did, you know, just regular books about people’s lives. But I never wrote a series because I was afraid I after writing one successful mystery, that I would be stuck, and I’d be writing, you know, my character and compromising positions with, Judith Singer goes Hawaiian in the 25th sequel. I didn’t want that. I wanted to try things out. So now that I’ve long been in my career this long, I thought I would really like to do a series because I want a family, another family.”

“Another family?”

“I mean, I have a great family. I have a husband who’s still practicing law. I have children, I have grandchildren, but I’m ready for another family.”

“And this series is going to be it?”

“It’s not just a one-book deal. I wanted more. So, I made Corie as rich and as complicated and as believable as she could be. It’s one thing to have a housewife detective. It’s another to have someone who lives in the suburbs, but who’s a pro. And she’s helped by her father, who was in the NYPD, who has a different kind of experience.”

“And that gives you a lot to work with. And, in an interesting way, at this stage of your life, another family to explore and live with.” I look at the clock. “Well, I guess we both need to get back to work.”

“This has been great. When you work alone all day, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone.”

We both laughed and we hung up. It was a break in the day. But a good break. I think Susan fed her ADHD a bit with the distraction, but for me, I learned a few things in just the passing conversation. Writers are wonderful. If you haven’t done it today, don’t text, don’t email, but pick up the phone and call a writer friend you know. I hung up the phone with Susan, invigorated, ready to get back to work. As she said, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone. As I would say, it’s nice to talk to someone and remember that, as writers, we are not alone, and we all have so much to learn.

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer and filmmaker and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Susan Isaacs is the author of fourteen novels, including Bad, Bad Seymour Brown, Takes One to Know One, As Husbands Go, Long Time No See, Any Place I Hang My Hat, and Compromising Positions. A recipient of the Writers for Writers Award and the John Steinbeck Award, Isaacs is a former chairman of the board of Poets & Writers, and a past president of Mystery Writers of America. Her fiction has been translated into thirty languages. She lives on Long Island with her husband. https://www.susanisaacs.com/

Author Amulya Malladi on “Research: Doing It, Loving It, Using It, and Leaving It Out”

Amulya Malladi interviewed by Clay Stafford

“I’m talking today with international bestselling author Amulya Malladi about her latest book A Death in Denmark. What I think is fascinating is your sense of endurance. This book—research and writing—took you ten years to write.”

She laughs. “You know, it was COVID. We all didn’t have anything better to do. I was working for a Life Sciences Company, a diagnostic company, so I was very busy. But you know, outside of reading papers about COVID, this was the outlet. And so that’s sort of how long it took to get the book done. I had the idea for a long time. I needed a pandemic to convince me that I could write a mystery.”

“Which is interesting because you’d never written a mystery before. Having never worked in that genre, I’m sure there was a learning curve there for you.”

“A lot of research.”

“You love reading mysteries, so you already had a background in the structure of that, but what you’ve written in A Death in Denmark is a highly focused historical work. It’s the attention and knowledge of detail that really made the book jump for me. Unless you’re a history major with emphasis on the Holocaust and carrying all of that information around in your head, you’re going to have to find factual information somewhere. How did you do that?”

“Studies.”

“Studies?”

“You’ll need a lot of the studies that are available. Luckily, my husband’s doing a Ph.D. He has a student I.D., so I could download a lot of studies with it. Otherwise, I’d be paying for it. Also, I work in diagnostic companies. I read a lot of clinical studies. So these are all peer-reviewed papers that are based on historic research, and they are published, so that is a great source, a reference.”

“But what if you don’t have that access?”

“You can go to your library and get access to it as well. If you’re looking for that kind of historic research, this is the place to go.”

“Not the Internet? Or books, maybe?”

“Clinical studies and peer-reviewed papers, peer-reviewed clinical studies, they’re laborious.”

“And we’re talking, for this book, information directly related to the historical accuracy of the Holocaust and Denmark’s involvement in that history?”

“You have to read through a lot to get to it. And it’s not fiction. They’re just throwing the data out there. But it’s a good source, especially for writers because we need to know about two-hundred-percent to write five-percent.”

“The old Hemingway iceberg reference.”

“To feel comfortable writing that five, you need to know so much more. I could write actually a whole other book about everything that I learned at that time. And that is a good place to go. So I recommend going and doing, not just looking at, you know, Wikipedia, and all that good stuff, but actually going and looking at those papers.”

“Documents from that time period and documents covering that time period and the involvement of the various individuals and groups.”

“When you read a paper, you see like fifteen other sources for those papers, and then you can go into those sources and learn more.”

I laugh this time. “For me, research is like a series of rabbit holes that I find myself falling into. How do you know when to stop?”

“The way I was doing it is I research as I write, and I do it constantly. You know, simple things I’m writing, and I’m like, ‘Oh, he has to turn on this street. What street was that again? I can’t remember.’ I have Maps open constantly, and I know Copenhagen, the city, very well. But, you know, I’ll forget the street names. That sometimes takes work. I’m just writing the second book and I wanted Gabriel Præst, my main character and an ex-Copenhagen cop, to go into this café and it turned into a three-hour research session.”

“Okay. Sounds like a rabbit hole to me.”

“You’ve got to pull yourself out of that hole, because, literally, that was one paragraph, and I just spent three hours going into it. And now I know way too much about this café that I didn’t need to know about. Again, to write that five-percent, I needed to know two-hundred percent. I am curious. I like to know this. So suddenly, now I have that café on my list because we’re going to Copenhagen in a few weeks, and I’m like, ‘Oh, we need to go check that out.’”

“So you’re actually doing onsite research, as well?”

“Yes. I use it all. I think as you write you will see, ‘Okay, now I got all the information that I need.’

“And then you write. Research done?”

“No. I was editing and again I was like, ‘Is this really correct? Did I get this information correct? Let me go check again.’”

“Which is why, I guess, your writing rings so true.”

“I think it is healthy for writers to do that, especially if you’re going to write historical fiction or any kind of fiction that requires research. Here’s the important thing. I think with research, you have to kind of find the source always. You know? It’s tempting to just end up in Wikipedia because it’s easy. You get there. But you know, Wikipedia has done a pretty decent job of asking for sources, and I always go into the source. You know you can keep going in and find the truth. I read Exodus while I lived in India. One million years ago, I was a teenager, and I don’t know if you’ve read Leon Uris’s Exodus, but there’s this famous story in that book about the Danish King. When the Germans came, they said, ‘Oh, they’re going to ask the Jews to wear the Star of David,’ and the story goes, based on Exodus, that the king rode the streets with the Star of David. I thought that was an amazing story. That was my first introduction to Denmark, like hundreds of years before I met my husband, and that story stayed with me. And then I find out it’s not a true story. You know? You know, Marie Antoinette never said ‘Let them eat cake.’ And so it was like, ‘Oh.’”

“Washington did not chop down the cherry tree.”

“No, and the apple didn’t fall. I mean, it’s simple things we do that with, right? With Casablanca, it’s like you said, you know, ‘Play it again, Sam.’ And she never said that. She said, ‘Play it.’ And you realize these become part of the story.”

“Secondary sources then, if I get what you’re saying, are suspect.”

“Research helps you figure out, ‘Okay, that never happened.’”

“When you say that you’re writing, and you’re incorporating the research into your writing sometimes you can’t, you’re not in a spot where the research goes into it. So, how do you organize your research that you’re not immediately using?”

“I don’t do that. I’m sure there are people who do that well. I’m sure there are people who are more disciplined than I am. I’m barely able to block my life. I mean, it’s hard enough, so you know if I do some research, I know there are people who take notes. I have notes, but those are the basics. ‘Oh, this guy’s name is this, his wife is this, he’s this old, please don’t say he’s from this street, he’s living on this street…’ Some basics I’ll have, so I can go back and look. But a lot of the times I’m like, ‘What was this guy’s husband doing again?’ I have to go find it. I won’t read the notes in all honesty, even if I make them. So for me, it’s important to go in and look at that point.”

“And this is why you write and research at the same time.”

“And this is why maybe it’s not the best way to do the research. It takes longer, like I said, you spend three hours doing something that is not important, but hey, that was kind of fun for me. I was curious to remember about Dan Turéll’s books, because I hadn’t read them for a while.”

“Some writers don’t like research. You like research. And for historicals, there’s really no way around it, is there?”

“I take my time and I think I really like the research. I have fun doing it.”

“Does it hurt to leave some of the research out?”

“Oh, my God, yes. My editor said, ‘You know, Amulya, we need the World War II stuff more.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, really? Watch me.’ So I spend all this time and I basically wrote the book that my character, the dead politician, writes.”

“This is an integral part of the story, for those who haven’t read the book.”

“I wrote a large part of that book that she is supposed to have written and put it in this book. I put in footnotes.”

“Footnotes?”

“My editor calls me and she’s like, ‘I don’t think we can have footnotes and fiction.’ I’m like, ‘Really?’ And she goes, ‘You know, you can make a list of all of this and put it in the back of the book. We’ll be happy to do that. But you can’t have footnotes.’ I felt so bad taking it out because this was really good stuff. You know, these were important stories.”

“So it does hurt to leave these things out.”

“I did all kinds of research. I read the secret reports, the daily reports that the Germans wrote, because you can find pictures of that. I kind of went in and did all of that to kind of make this as authentic as possible, and then she said, ‘Could you please, like make it part of the book, and not as…’ She’s like ‘People are going to lose interest.’ So yeah, it does hurt. It really didn’t make me happy to do that.”

“You reference real companies, use real restaurants, use real clothing, use real drinks. You use real foods. Do you have some sort of legal counsel that has looked over this to make sure nobody is going to sue you for anything you write? Or how do you protect yourself in your research?”

“When I’m being not-so-nice about something, I am careful. I have not heard anything from legal. Maybe I should ask tomorrow. I think Robert B. Parker said this in an interview once: ‘If I’m going to say something bad about a restaurant, I make the name up.’”

“Circling back, you do onsite research, as well.”

“Oh, yeah. I’ve been to Berlin several times, so I know the streets of Berlin. I know this process. I know what they feel like. It’s easier to write about places you’ve been to, but the details you will forget. Even though I know Copenhagen very well, I still forget the details. ‘What is that place called again? What was that restaurant I used to go to?’ And then I have to go look in Maps, and find, ‘Ah, that’s what it’s called here. How do they spell this again?’ But I think, yes, from a research perspective, if you are wanting to set a whole set of books somewhere, and if you have a chance to go there, go. Unless you’re setting a book in Afghanistan, or you know, Iraq, then don’t go. Because I did set a book partly in Afghanistan and I remember I talked to a friend of mine. She’s a journalist for AP and she said, ‘Oh, you should come to Kabul.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I don’t think so, just tell me what you know so I can learn from that and write it.’ She’s like, ‘You’ll have a great time on it.’ And I said, ‘I will not have a great time. No, not doing that.’ But I think, yes…”

“When it comes to perceived safety, you’re like me, an armchair researcher. Right?”

“Give me a book. Give me a clinical study. Give me a peer-reviewed paper, I’ll be good.”

“What advice do you have for new writers?”

“Edit. Edit all the time. I’ve met writers, especially when they are new, they say things like, ‘Oh, my God! If I edit too much, it takes the essence away. I always say, ‘No, it just takes the garbage away.’ Edit. Edit, until you are so sick of that book. Because, trust me, when the book is finished and you read it, you’ll want to edit it again because you missed a few things. I tell everybody, ‘Edit, edit, edit. And don’t fall in love with anything you write while you’re writing it because you may have to delete it.’ You know, you may write one-hundred pages and realize, I went on the wrong track and now I have to go delete it.”

“And take out the footnotes.”

“Yeah, and take out the footnotes.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, literary theorist, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Clay’s book links: https://linktr.ee/claystafford

Amulya Malladi is the bestselling author of eight novels. Her books have been translated into several languages. She won a screenwriting award for her work on Ø (Island), a Danish series that aired on Amazon Prime Global and Studio Canal+. https://www.amulyamalladi.com/

Amulya’s book link: https://linktr.ee/amulyamalladi

Author Chris Grabenstein on “Switching Genres and James Patterson’s Advice on How to Make a Million Dollars”

Chris Grabenstein interviewed by Clay Stafford

Author Chris Grabenstein grew up outside Chattanooga, Tennessee. So did I. But we didn’t know each other until we met one year at Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. We quickly learned we had much in common, including a sense of twelve-year-old-boy humor. Chris was learning his craft and making his way writing for grown-ups when I met him then. Really funny stuff. It was the John Ceepak mystery series with such delightful titles as Whack a Mole, Tilt a Whirl, and Mind Scrambler. I liked him so much and he was such a personable guy, I brought him back several years later as a Guest of Honor at Killer Nashville and he had, not surprisingly, changed audiences on me. He was now a multiple award-winning #1 New York Times bestselling children’s author. We sat down together to talk about co-writing with James Patterson, his transition from writing for adults to middle-grade readers, daily word counts and revising schedule, what’s important for him, his advice for writers, and James Patterson’s advice on how to make a million dollars.

“Chris, you’ve got this great series going for adults, and suddenly you write for kids. What caused you to switch, or were you writing both at the same time?”

“It was actually a major switch. I have like twenty-four nieces and nephews, and at the time they were all under the age of eighteen, and they said, ‘Uncle Chris, can we read your books?’ No, no, there’s a few f-bombs being thrown around, there’s a lot of adult situations. There was an editor who was looking for ghost stories for middle grade readers, kids ages eight to twelve. The third book I wrote had gotten rejected by everybody. It was a ghost story. So my agent said, ‘Well, Chris wrote a ghost story, but it’s not for middle grade readers,’ and the editor said, ‘Well, if the story is any good we can turn it into one.’”

“That’s kind of a novel approach. And certainly serendipitous.”

“Yes. And so he read my third book, which was 110,000 words long, and said, ‘This would be a great book for middle-grade readers. You just have to get rid of the adult situations, the adult language, and cut it down to like fifty-thousand words.’”

“And that’s how you switched from adult to children’s books?”

“My agent said, ‘Do you want to do that?’”

“That’s like cutting sixty-thousand words out.”

“By the time I wrote that third book, I’d already spent a year working on it, so I knew I was going to have to spend another year on it. But my nieces and nephews, they really wanted to read something, so I said, ‘I’m going to do it.’”

“There’s certainly more to it than just cutting words.”

“I always recommend if you’re going to try a new category, get to know it a little bit, read a bunch of books. So I started reading a lot of books for eight-to-twelve-year-olds. I said, ‘Maybe I can do this’ and I put in a couple of fart jokes.”

“There’s got to be more than that.”

Chris laughs. “The kids have got to be in charge of the story. They’ve got to be the one solving whatever the mystery is. Carl Hiaasen wrote for that age group, Hoot, and there’s a great book called Holes by Lois Sachar. I read those, and they helped me get the sense of writing for children in that age group. And as I wrote, I was tapping back into that Mad Magazine twelve-year-old kid that I used to be, and I was having such a blast, too, and I said maybe I should be doing this.”

“So not only were you saving the manuscript, you were having fun.”

“I wrote it. We turned it into that editor who was looking for middle grade books, but his boss no longer was looking for ghost stories.”

“You’re kidding.”

“So it died once again. My wife and I don’t have any kids, but we borrowed two from our friends, Kath and Dave, who had kids who were like nine and ten, and they loved this book. They read the manuscript, you know the draft of it, and they were running around their church going, ‘We read the best book. We read the best book.’”

“Sounds like they were telling God.”

“It turns out a member of their congregation happens to be the head of the children’s department at Harper Collins, and she hears these two kids raving about some new book. My buddy Dave is a fire chief here in New York City, and he’s rather gregarious and not shy. In fact, he was one of the inspirations for Ceepac, the character of Ceepac. He said, ‘Oh, yeah, my buddy Chris wrote the best book. The kids love it more than anything they’ve ever read.’ And so the president of Harper Collins Children interviewed the two kids.”

“What?”

“Yes. She wanted to talk to me about it. My agent then called up one of his friends he knew at Random House who does children’s books and says, ‘You know, Harper Collins is interested in this thing my guy, Chris, wrote,’ and we got an offer from both houses, and Random House had a two-book offer.”

“And that’s how you started writing for kids.”

“That’s how I started writing for kids. Then, Harper Collins, that editor who we weren’t able to work with, liked it so much said, ‘Could you do something for me?’”

“You’re kidding.”

“That’s how my series, Riley Mack and the Other Troublemakers started was with her, and I did four ghost stories for Random House.”

“Ghost stories again. Full circle. So how did you get involved co-writing with James Patterson? You had previously worked in advertising with him. Was that how you had the connection?”

“Not exactly. I went down to teach at his son’s school. And if you’re writing for kids, you want to do a lot of school visits. It helps book sales and also helps you keep in touch with the kids who are going to be in your audience. And so the Palm Beach Day Academy, where James Patterson’s son was going to school, wanted me to come because they had heard that I used improvisational comedy, and their kids at the Palm Beach Day Academy were so success-oriented, they wanted them to loosen up a little bit. So they had me come in and do my improv show, and I think Jack Patterson went home and said to Jim—I call him Jim, because that’s what we called him in advertising—that guy Chris Grabenstein is pretty funny.”

“Interesting.”

“And they just happened to have their book fair the same night that I was there, so they invited me to come. James Patterson was the guest speaker. I sat down in the front row with his wife, Sue, who used to work at J. Walter Thompson, too. I think Jim remembered, ‘Oh, yeah, Chris was a pretty decent guy. He was pretty talented, and he was easy to work with’ because that’s Jim’s criteria.”

“Nice criteria. I use it in my own company. Makes the days go better.”

“It’s like life’s too short. Advertising was such a royal pain and publishing can sometimes be that. He just wanted co-authors who are good at what they did and were not prima donnas, and were not divas, and just did it for fun. We have a good time, and we’ll do the next one. So that’s how I got started writing books for James Patterson. He had me audition on the fifth book in one of his other series, and that went well, and then we did, I Funny, and we did six books in that. While we were working on I Funny the Treasure Hunters thing came up. We did nine books, and we’ve done three dozen books together.”

“How do you find the time? And when you say you wrote these books, we’re talking multiple drafts of each book, not just a first manuscript.”

“It’s that old advertising discipline. People get shocked when I tell them every commercial you saw of mine that made it to air, I probably wrote between one hundred and three hundred scripts that died. Either my social creative director, my creative director, my executive creative director, the marketing people, the account people, the salespeople; somebody killed it. It could have been the president of Miller Brewing Company. Somebody killed it, and you just get used to ‘All right. There’s another idea. There’s another idea,’ and you develop a discipline.”

“And a thick skin.”

“The Brits call it bum glue, where you sit down every day for a prescribed period of time, and you write, and I do that every day. I try to write two-thousand new words every day, and I start the day going over the two-thousand words I wrote the day before, basically to get back into the zone. Doing a little bit light editing on those helps me to say, ‘Okay, I remember where we are. Oh, and this was gonna happen next.’”

“It helps when you have a plan to sit down each day, certainly. I get that.”

“Someone wrote, ‘When you know what’s gonna happen next, that’s when you should stop writing for the day, you should just like, walk away,’ and for me it’s two-thousand words, and I usually start getting a little fatigued at that point.”

“But these are not necessarily words you’re going to keep. Because, as you said, you have great ideas and then not so great. But still, two-thousand words is a lot of words. Is that like the adamant goal? Two thousand every day before I stop?”

“Yes, if I’m in the groove. If I’m traveling, or I’ve got copy editing that needs to be taken care of, or lots of school visits, then I might do one-thousand.”

I laugh. “Showing yourself some grace.”

“Two-thousand words a day goal is when I’m drafting. When I finish my first draft, usually aiming for a page or word count that I will totally overshoot, I begin the real editing. I believe in the Stephen King credo: ‘Second draft equals first draft minus ten-percent.’ I always cut at least ten-percent. The manuscript I am working on now, it’ll be more like twenty-percent, because I really overwrote. I will spend a week or two cutting, editing, revising. Then I show the manuscript to my wife, my first reader. She gives me notes about anything that confused her or took her out of the story. I make more cuts and tweaks. Finally, I send it to my agent and editor. The editorial process will go on for at least two to three more revisions. If the editor sees major work to be done, that could go up to seven or eight back-and-forths, with major structural changes.”

“That’s a lot of drafts. Many beginning writers don’t realize how many drafts you sometimes have to go through.”

“Escape from Mr. Lemoncello’s Library went back and forth seven times and took over two years to complete after I had finished what I thought was my perfect first draft!”

“And that was also your first movie. Any advice you’d like to pass on to us writers?”

“One of the best books I ever read about writing was Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft where he writes about his story, and then in the middle part, he sort of blocks out how you can write, because I never thought I could write. You know, those first adult books for seventy-, eighty-, ninety-thousand words long was really different for me because at the same time I was writing those, I was writing commercials. Commercials are seventy words you’ve got if you talk wall-to-wall in a thirty-second commercial, which you never want to do. You’ve got seventy words to play with, but Stephen King really breaks it down nicely.”

“For the bigger book.”

“He does the analogy of building a house where, if you come every day and put one brick down, make sure it’s level, plumb and square. Come back the next day, put down the brick next to it, make sure it’s level, plumb and square. If you do that consistently for five days. You’ll have one row, you know. Then before long we have a wall. After that you’ll have four walls, and then you’ll figure out how to put a roof on.”

“As an author, what’s most important to you?”

“Two things, I think. Number one, that I’m entertaining my audience because I come from being a performer. I always entertain my audience. The second, that I get to keep doing it. I don’t care so much about the big advances and stuff. I even told one of my agents that, and they went, ‘What?’ I don’t care about that because I have confidence that if the book’s good and people like it, we’ll earn some money down the line. But I just want to be able to keep writing.”

“And that’s the real reason to write, isn’t it? Because you love it for the sake of writing.”

“I will share what James Patterson taught me. We used to have a training program in advertising. I don’t think anybody has the money to do that anymore. And he came in and gave this lecture once to everybody: creative people, account people, media people, research people, all the new hires. We’re all together, like twenty or thirty of us, and we had different lectures every week. So, James Patterson is going to come in now and talk to us about how to be creative. He comes in, and back in those days, he had a big, bushy beard, big old, kind of curly, bushy beard. He came up to the podium. We’re at Madison Avenue, big, you know, office building, just like Mad Men in the conference room, and he says, ‘All right. I’m going to teach you how to make a million dollars a year in advertising. The secret is…’ Before he could say another word, the door flies open, and this knucklehead comes running into the room with a banana cream pie and slams it in James Patterson’s face. And remember he’s got a beard, so he’s got all this cream, and crust, and stuff, and yellow goo just dripping down his beard, and we’re all going, ‘That guy is so fired. He is going to be so fired.’ Jim cleans himself up a little bit. He said, ‘All right. I just showed you how to make a million dollars a year in advertising. Throw a pie in their face, and once you have their attention, say something smart.’”

“Wow.”

“I never forgot that lesson. That’s why all my stories, all my commercials, start with some kind of boom, something that grabs the reader’s attention, and once you have their attention, they’ll stick around for the exposition, and to learn a little bit more. So many mysteries I read start out with, ‘I’m working in this small town, where I run the donut shop. It’s also a dry cleaner, and I’ve been doing it for all these years.’ Have somebody come in and, I don’t know, have a donut explode or something. Get my attention, and if you do that, I’ll stick around for the rest of your story.”

I smile. “And there’s nothing better for a kid than an exploding donut. I can see why the kids love you.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, literary theorist, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Clay’s book links:

https://www.amazon.com/Killer-Nashville-Noir-Clay-Stafford/dp/1626818789/ref=sr_1_1?tag=americanbla03-20

Chris Grabenstein is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of the Mr. Lemoncello, Wonderland, Haunted Mystery, Smartest Kid, and Dog Squad series. He has also co-authored three dozen fast-paced and funny page turners with James Patterson. https://chrisgrabenstein.com/

Chris’s book link:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/588883/the-smartest-kid-in-the-universe-by-chris-grabenstein/

Killer Nashville Interview with David Baldacci

Clay Stafford Talks with #1 Global Bestselling Author David Baldacci on Developing Characters

I recently had the opportunity to spend some time with David Baldacci, #1 bestselling crime and thriller novelist. We talked about his new novel, Simply Lies, and then other aspects of writing. Baldacci has had major success in writing both series and standalone novels and he shared with me his insight about the key to both these types of storytelling: the characters. Simple enough, but it opened up questions for me. “I get characters must hold a readers’ attention throughout the plot of a novel and carry one book in a series to the next, but how does a writer cultivate a character to be able to do this? When we chatted earlier, you seemed to imply that the process was more spontaneous.”

Baldacci shrugs slightly. “I really am much like, let’s see how it goes… Let me just wake this person up at the start of the day and walk them through what I want him to do. Let’s see what he does. Let’s see how this stuff ticks. It’s like you’ve got this blob of clay. You spend a little time with it and then you start chipping some stuff off here. Let’s see how the world that I’ve created for him and I’m putting him or her through is shaping him or her. And then we’ll figure out what sort of personality flaws and interesting personality traits this person might have. It’s always important to put the characters into the world that they’re going to be in for 400 plus pages and see how it works out.”

“So you just let the writing process mold the character itself naturally. But what does that mean in terms of planning?”

“Early on, I did the personality sketches and chapter outlines, but I just realized that none of it really was working for me. I don’t sit down and do character personalities with seventy-seven different ideas of what this character should be because it’s overkill and you’re never going to remember it all. You’re going to keep referring back to this checklist of stuff and you’ll realize that the majority of it you don’t even need or want in this person.”

“So is it more efficient to ditch the outlines and charts?”

“You’re going to get a better feel for this character about how they actually should come across to the reader and what you think they’re going to need in order to get through this novel in a plausible way.”

“Do you have other tactics to build and enhance characters?”

“If I have one main character like Amos Decker or Will Robie, I give them a lot of baggage in their own personal background that I can then exploit later in future books. So if you were to start a book and you really want it to be a series, you have to sort of build up that stuff in that first novel. It can be through backstories of one character or multiple characters that you’re going to exploit in future books. Or it could be something about a physical characteristic, an intellectual characteristic, or the people that the main character will meet on an ongoing basis because of the work that they do, and they can be exploited in the future books and build it in.”

“I’d think a perfect example of this is your character of Amos Decker, who had a blow to the head in a football incident, which caused hyperthymesia, perfect recall, and synesthesia.”

“It changed the way his brain operates so he has a lot of personal demons in every book. What I try to do with Decker is show his brain constantly transforming itself because of the brain trauma so every book he has to deal with something new happening in his own mind and his own personality, which continues to change on him. You can imagine how difficult and frustrating that could be. Plus, I have new elements about how his mind works to come in every novel and I have a lot of personal baggage.”

“So practically speaking, how do you pull all this together, if I were going to sit down and write something right now…”

“Do this judiciously. You don’t want to blow everything up in the first novel. You need to turn the tap on and turn it off. Be thinking about those things and lay Easter eggs throughout a series of books, and they’ll only be resolved in future books. Plant some things and foreshadow some things in earlier books that you can take advantage of in later books.”

“So for you, planning involves more strategic backstories and personality traits than charts, outlines, and lists.”

“You don’t have to do it one way. And what works for someone else may not work for you. During the course of your career, your process actually may change a little bit. You may become more outline oriented or less outline oriented further along you go because there’s no perfect way to do this. You just sort of jump in. You have a little bit of structure about the things you want to accomplish, things you want to write out, things that you might see coming up ahead and then go from there.”

“You really have a fondness for your characters. It comes through.”

“When you create a character, it’s almost like adopting someone into your family. You’re going to spend a lot of time with that person on a very personal basis and you need to make sure that it’s a sort of person you want to hang out with for a while. You have to feel passion and interest about what they’re going to be doing in the novel. The character is the only opportunity you get to connect with the reader on a human level. The plot does not do that for you. The characters do. So, if you write a character who never makes a mistake, you’re going to lose the reader at page 10. If you have a character who gets knocked down and then gets back up and tries to keep going, you’re going to have the readers in your pocket.”

I smile. “Which you certainly do.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer and filmmaker and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

David Baldacci is a global #1 bestselling author with 150 million copies sold worldwide; his newest thriller, SIMPLY LIES, was published April 18, 2023. https://www.davidbaldacci.com/

Submit Your Writing to KN Magazine

Want to have your writing included in Killer Nashville Magazine?

Fill out our submission form and upload your writing here: